Disparities in Multiple Myeloma

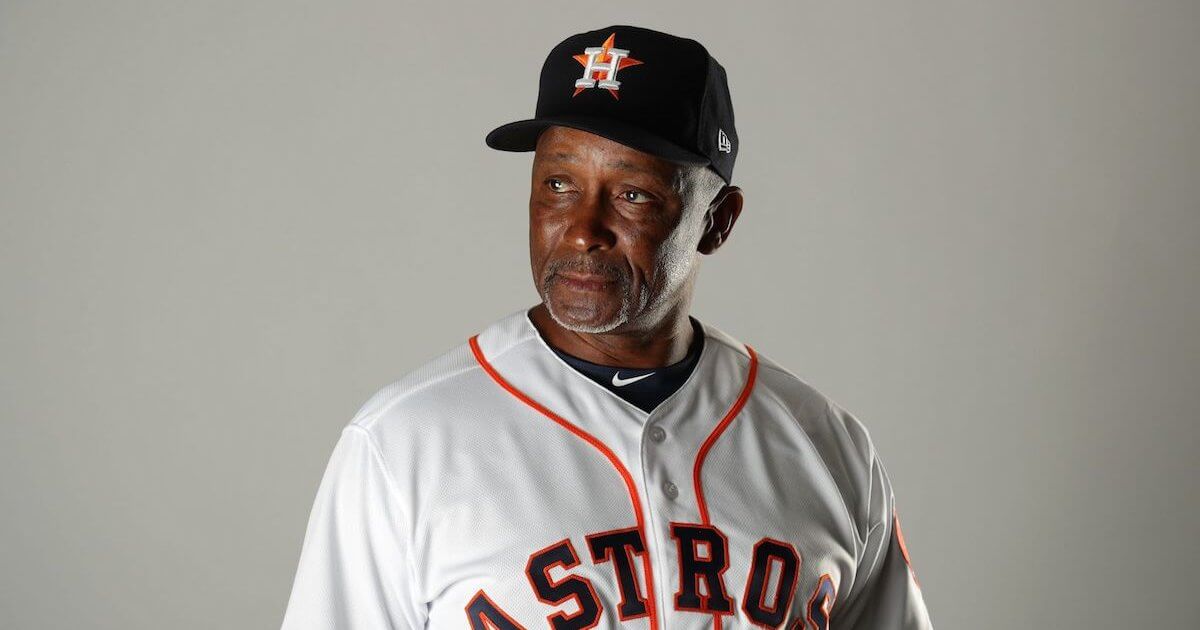

- Houston Astros’ Gary Pettis is currently battling multiple myeloma a rare blood cancer.

- Multiple myeloma is the most common blood cancer affecting Black Communities.

- Experts tell SurvivorNet that Black patients need fair access to treatment options.

Multiple myeloma is a very rare blood cancer which causes white blood cells in your bone marrow, called plasma cells (the cells that make antibodies to fight infections), to grow out of proportion to healthy cells. With the larger number of abnormal cells, it keeps healthy cells from fighting infections in the body, and can cause the disease to spread to other parts of the body. While this disease is considered rare, it’s the most common type of blood cancer that impacts Black communities, and Black individuals are twice as likely to be diagnosed compared to white patients.

Read More

Clinical Trials & Black Communities

Clinical trials can be life-saving resources for cancer patients facing a rare and difficult diagnosis. However, many Black communities are still suspicious of clinical trials, and it dates back to the 1932 Tuskegee syphilis experiment. More than 600 Black men in Alabama were enrolled in the study by the U.S. Health Service, but the men were never told what the study was truly about and they were never given the proper treatment to cure the disease. Since the infamous experiment, it’s understandable that Black patients are distrusting of clinical trials, and compared to the general population, Black patients and other minorities are underrepresented in clinical trials. However, experts stress how valuable these trials can be.

“[A study] showed that if people participated in clinical trials for myeloma, the differences between any outcome in caucasian or Black patients sort of goes away, that they both derive benefit from participation in a clinical trial,” Dr. Natalie Callander, a board-certified medical oncologist at University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, tells SurvivorNet.

The first step to address this underrepresentation is to slowly rebuild trust in the Black community. Physicians need to make clear that they acknowledge inequality Black communities and other minorities have faced in the healthcare system, and reassure patients they have no plans to take advantage of it. Above all, patience is key.

Dr. Otis Brawley explains how physicians can build trust with patients

Navigating Multiple Myeloma Treatment

Once receiving a multiple myeloma diagnosis, there’s a few steps to the process. The first approach some physicians take is to give patients combination therapy, which means using multiple drugs. This therapy is called RVD, consisting of Revlimid (lenalidomide), Velcade (bortezomib), and Dexamethasone. The combination of these three drugs has been shown to be highly effective as the first treatment myeloma patients receive that doctors agree it should be the standard of care.

If patients respond well to combination therapy, the next step in the treatment process is often a stem-cell transplant. There are two forms of transplants that could be taken: autologous stem-cell transplant and allogenic transplant. During an autologous stem-cell transplant, your own healthy stem-cells are removed from your bone marrow prior to chemotherapy and then are re-inserted into the bone marrow following therapy. During an allogenic transplant, stem-cells will be taken from a healthy donor that closely matches your body's cell type and may even be related to you.

The chemotherapy and subsequent stem-cell transplant take about two weeks and can be difficult to tolerate. Due to the initial high dose of chemotherapy, you will have to endure hair loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a 50% chance of infection that can be treated with antibiotics. Patients typically recover by the end of the third week and are released from the hospital.

Dr. Sagar Lonial explains what to expect during a stem-cell transplant for multiple myeloma

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.