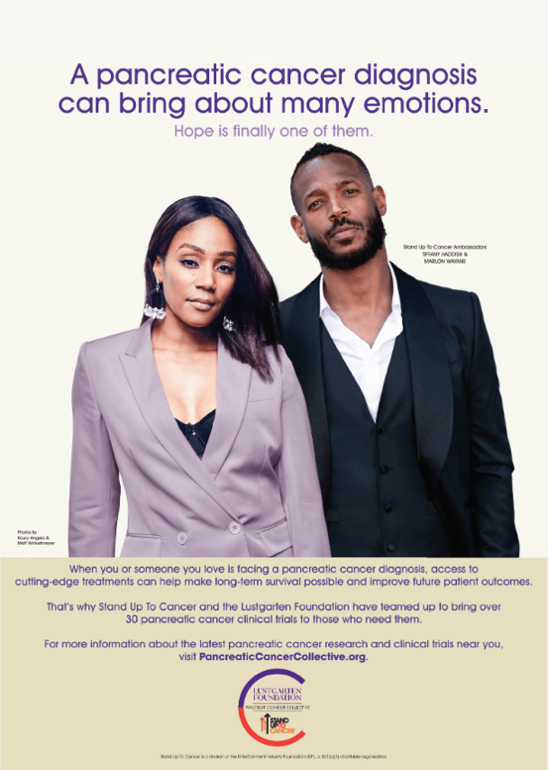

Tiffany Haddish and Marlon Wayans are using their celebrity to raise awareness about pancreatic cancer trials in a new campaign debuting this week with Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C).

Both Haddish and Wayans have previously worked with the organization and shared their stories about losing loved ones to the disease.

"Last year I lost a dear friend to this disease who profoundly impacted my career and life. Her loss is part of my inspiration for becoming an advocate for taking care of your health,” said Wayans.

Haddish spoke about losing a family member to the disease last month while attending the World Series on behalf of SU2C.

“We here at the World Series for the @su2c foundation and @braves,” wrote Haddish in a post she shared across her social media accounts.

“I stand up for my favorite Auntie Myrtle. she passed away from breast cancer when I was young. She would be so happy right now cause I am doing everything we used to talk about. I Love and miss you, Great Auntie Myrtle.”

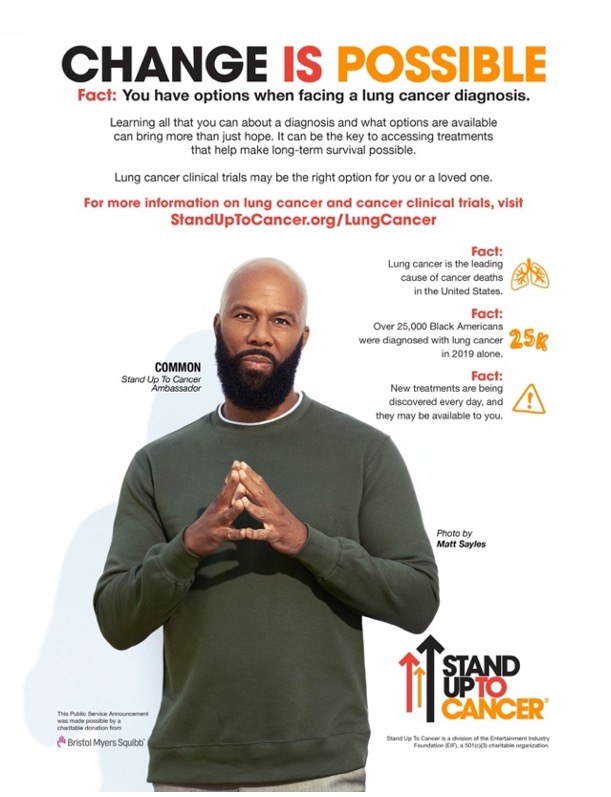

Haddish also joins boyfriend Common as a SU2C ambassador, whose lung cancer PSA launched earlier this month. Common lost his father in 2014 to prostate cancer.

Wayans and Haddish will appear in a new print and radio PSA to bring awareness to the “cutting-edge treatments available through pancreatic cancer clinical trials.”

Additionally, this new campaign aims to increase awareness in Black communities where there is a 30% higher pancreatic cancer incidence rate than any other racial or ethnic group.

SU2C is also hoping to address one of the most glaring issues in cancer care – the lack of diversity in clinical trials. The PSA will direct viewers to a website that lists some of the trials across the country.

That effort, the Pancreatic Cancer Collective, is the work of SU2C in conjunction with the Lustgarten Foundation. The two have been teaming up to advance research into pancreatic cancer for close to a decade now, funding more than 400 investigators from nearly 70 leading research centers worldwide.

Diversifying Clinical Trials

A panel of experts discussed the need for more diversity among participants in clinical trials earlier this year when Survivor Net partnered with Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health for the 'Close the Gap' conference.

The lack of diversity in these trials is both a product of, and results in, the disparities in treatment and survival rates for non-white cancer patients.

Panelist Berangere Pierre-Louis, a patient navigator at NYU Langone Health, summarized just a few of the biggest hurdles that keep members of the black community in particular from participating in studies.

“They're afraid to find out whether or not they have a diagnosis, believe it or not, and we can try to tell them the sooner you get diagnosed the better because then you have better chances of survival, you have better chances of better options, but because of their current living situations… they just don't want to face it at this moment," said Berangere. "We have a lot of single parents, we have a lot of undocumented immigrants who are single parents as well. They feel that if something happens to them, what's gonna happen to everybody else."

There is also the very justifiable issue of mistrust among members of the Black community.

The example most often used to illustrate this point is the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. That study consisted of 600 men, 399 of whom had syphilis.

Participants were not informed of what they had been infected with and their consent was not obtained by those who oversaw the study.

In exchange for their participation, the men received free medical exams and meals as well as insurance to cover the cost of their burial but not a funeral service.

The study continued for the next 40 years, and the men were barred from receiving penicillin – a known treatment for the bacterial infection – after it became widely available during World War II.

President Bill Clinton would eventually issue a formal apology for the study in 1997, stating at one point in his remarks “how adrift we can become when the rights of any citizens are neglected, ignored and betrayed.”

The reverberations of that experiment and the mistrust it sowed were most recently felt earlier this year as the COVID-19 vaccine began to roll out.

"We have to understand that for members of our communities there is a justified reason for fear," noted Bernagere.

That comment rang particularly true this past year with the hesitancy among a number of non-white Americans when it came to getting the COVID vaccine.

The only way to finally quell those fears, guarantee diversity in these trials, and perhaps one day assemble a participant pool that is representative of a given population is, of course, equity.

Pancreatic Cancer Risk

With a five-year relative survival rate of only 9% in the United States, pancreatic cancer remains one of the deadliest forms of the disease. Incidence rates for the disease rose by about 1% per year from 2006 to 2015.

“Pancreatic cancer is still uncommon enough that if you were to screen everybody you would end up with a lot of false positives,” explains Dr. Anirban Maitra, co-leader of the Pancreatic Cancer Moon Shoot at the MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Even with a fantastic biomarker test that you had, even if it was 99% sensitive and 99% specific, you would still have a lot of false positives.”

That is not meant to deter people from screenings, especially those whose relatives have been diagnosed with the disease.

“If somebody has two first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer,” Dr. Maitra says, “their risk is already double digits higher than the average population. If they have three family members it’s almost 34 percent higher than the average risk population.”

The presence of cysts on the pancreas also carries an increased risk of cancer, though in most cases those growths are completely benign.

Challenges to Screening for Pancreatic Cancer

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.