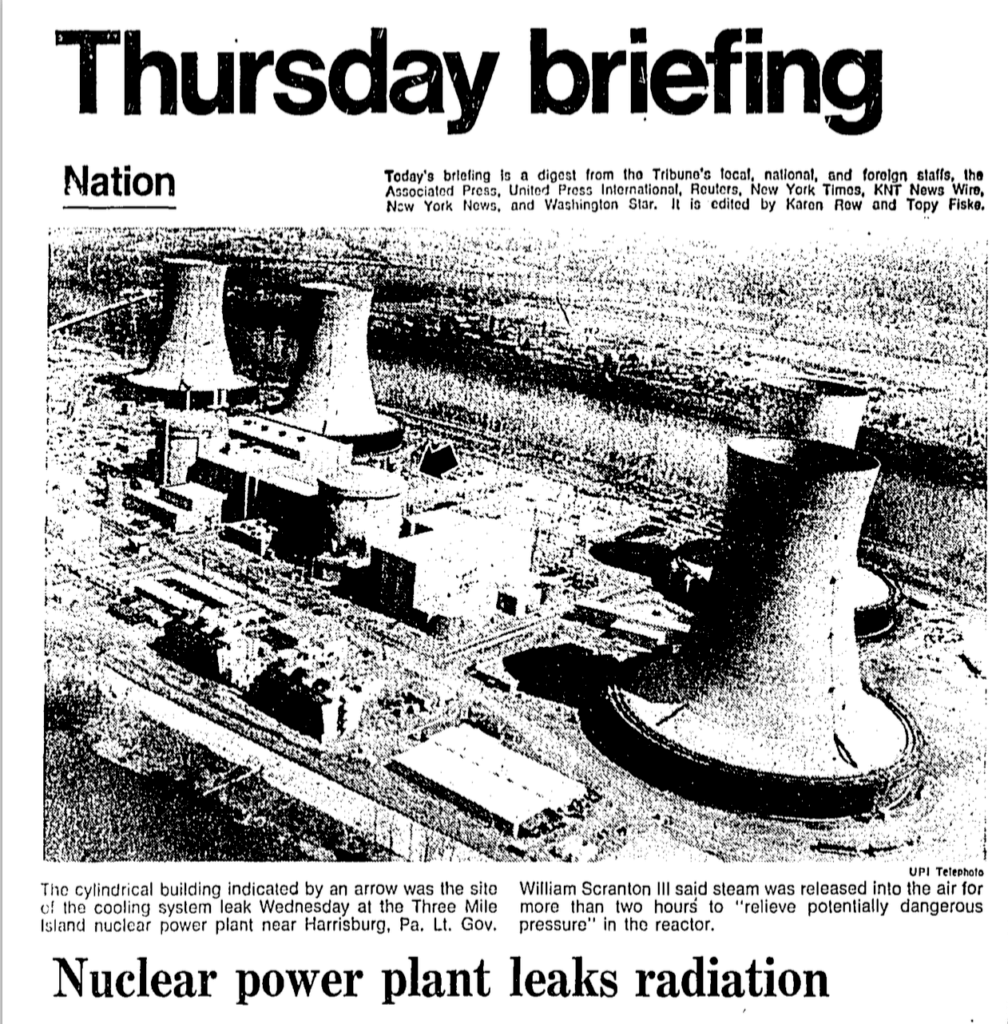

40 years after the worst nuclear power disaster in American history occurred on Three Mile Island, people from the area are still getting sick, and the incidence of thyroid cancer is rising faster in Pennsylvania than in the rest of the country as a whole, according to a study published in 2014.

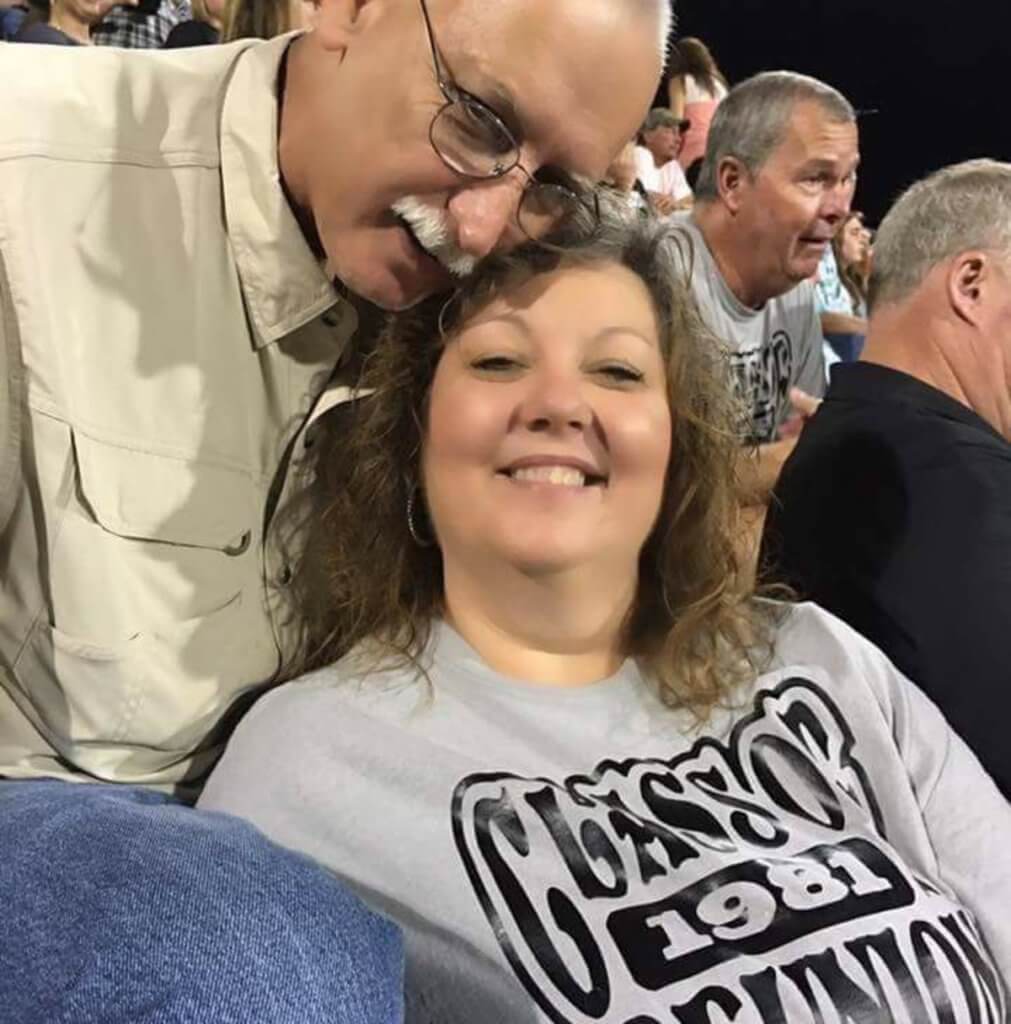

“I think people were irresponsible when it happened,” says Lucy Polston, a fifty-five year old thyroid cancer survivor, who lived near Three Mile Island in the Susquehannah River Valley, Pennsylvania during the time of the disaster. “They made it sound like everything was okay and then they had us evacuate.”

Read More

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland at the bottom of the neck, and it produces hormones that help the body regulate some of its other functions — heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature and weight. Thyroid cancer is generally considered to have a very good prognosis, with over a 99 percent survival rate (survival for 5 years after after diagnosis). “It’s not the greatest thing to have but it’s extremely treatable,” says Dr. Moadel. With this disease, she says, “you have your whole life ahead of you.”

People with thyroid cancer who lived in the area around Three Mile Island, now owned by Exelon Corp., at the time of the meltdown, had genetic mutations that were familiar to researchers from other nuclear events, according to the study. “Findings were consistent with observations from other radiationâ€exposed populations,” says the study. “These data raise the possibility that radiation released from [Three Mile Island] may have altered the molecular profile of [thyroid cancer] in the population surrounding [the power plant].”

Exelon Corp. released a statement saying that it plans to shut down the Three Mile Island power plant in 2019 because the plant is no longer profitable, unless Pennsylvania provides subsidies to keep it open.

Lucy Polston, who was fifteen at the time of the partial meltdown, was treated for thyroid cancer in 2018. “They usually give you one radioactive iodine pill but they gave me two. They hand you a led container open the door and close it, and they couldn't put anyone in the rooms next to or above or below mine,” Polston says. “The doctor told me, ‘When I dump these pills in your hand, you swallow them right away. Do not let them lie in your mouth, they have to go right down.’ Nobody could come visit. You have to flush the toilet two or three times [every time you use the bathroom] for a week because of all of the poison coming out of your body.”

“My brother was in the clean up crew, and he died from cancer,” she continues. “They had to clean up whatever rooms the accident was in. I'm sure they wore suits and stuff. [His cancer] started in his tonsils. He lived about three year with it before he died.”

Polston’s primary memory of the event is officials telling her not to worry. “We had gotten news it was okay to start with, we were allowed to be outside playing and stuff when it first happened.”

But soon after, she says, the tone of the instructions began to change. “Then they told us we had to go inside, close the doors, close the windows, and then we had to evacuate.” Her family was told to get at least 75 miles away from the site, so they picked up and went to her grandmother’s house, which was just inside that 75 mile radius. It was the only place they had to go.

Clean Up Crew After Three Mile Island Disaster Wearing Suits To Protect Against Radiation.

When Polston first noticed something wrong with her neck, the people around her didn’t think too much of it. “I had a goiter on my neck for seven years. And I'm kind of large so no one would take me seriously and kept saying it was just fatty tissue,” she says.

But when her symptoms worsened, she started seeking out second opinions about her health, and eventually found an endocrinologist who screened her body. After blood work and a biopsy, they found thyroid cancer. “Most people don't die from thyroid cancer. But it could come back anywhere in my body because of the type I had,” says Polston.

Although Polston moved to Florida, she still goes back to visit her family members who live in Pennsylvania. “I go visit. I've got brothers up there, a sister, and my real dad,” she says. Polston’s father and sister-in-law have survived bladder cancer and cervical cancer respectively. “And we didn't have any cancer in our family before that.”

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.