People who are diagnosed with cancer have better memories than people with no history of cancer, according to a new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. This probably runs contrary to what you’d think especially if you’ve experienced the memory fog of “chemo brain“which the article points out is, for most people, a temporary blip in the overall superior-memory trend.

Few would argue that the side effects associated with cancer treatment are unpleasant, to say the least. Fatigue, pain, hair loss, neuropathy, lower immune function, skin rashes, and more. The list of "bummer" cancer symptoms is not a short one.

Read MoreThe study enrolled a total of 14,583 people (both men and women), all of whom were born before 1949. Importantly, at the beginning of the decade-long study, none of these people had a history of cancer (which was purposeful; the researchers wanted to study how cancer affects memory before, during, and after diagnosis).

Over the course of the 11.5 years, the researchers carefully monitored memory function using a combination of cognitive tests and interviews. During that time, 2,250 participants ended up receiving cancer diagnoses and 12,333 remained cancer-free.

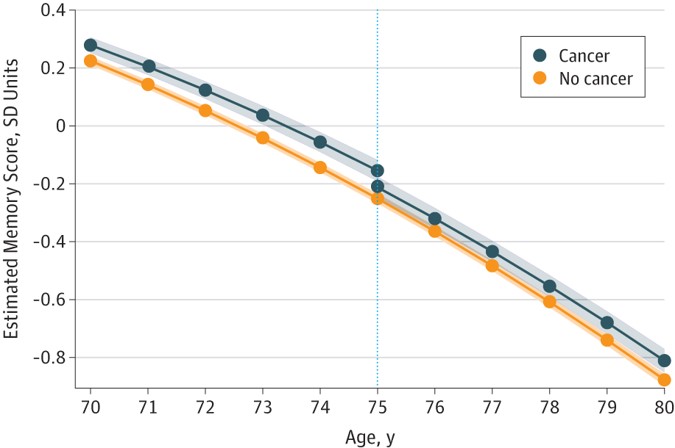

Interestingly, before cancer, those who ultimately would be diagnoses experienced memory decline at a 10.5 percent slower rate than those who would never be diagnosed. Then, at the time of diagnosis, the researchers saw a sharp temporary drop in memory function among those with cancer (perhaps, they noted, due to treatment effects like temporary cognitive impairment, or chemo brain). But afterward, the rate of gradual memory decline still remained slower than those who were never diagnosed with cancer.

This Sounds Great, But What About 'Chemo Brain'?

Many people with cancer report experiencing foggy memories and slower cognitive function during treatmentknown as “chemo brain“especially chemotherapy and radiation, which work by killing cancer cells (and often end up killing a lot of healthy cells in the process). The condition is real, and research shows that it happens because these cancer treatments damage the DNA within healthy cells in your body, which can affect mental abilities.

But chemo brain is usually also temporarybecause the human body is remarkable at recovering. Dr. Douglas Blayney, a medical oncologist at Stanford Health Care, previously told SurvivorNet that "the dysfunction is usually temporary and clears within a year of starting treatment."

This explains why the researchers saw a sharp dip in memory function right around participants' diagnosis, but then saw the "better memory" trend resume again after cancer (albeit at a lesser rate).

So yes, during treatment for cancer, memory can fade and fog, but it's not your cancer causing it, it's your treatment.

But Why Would People With Cancer Have a Better Memory?

Because the study was an observational one, researchers couldn't pinpoint for certain the cause of the inverse association, but based on past research (including a 2014 study that found that individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease had a 42 percent decreased risk for cancer, while patients with a history of cancer had a 37 percent decreased risk for Alzheimer’s) they suggested that the counterintuitive results could be due to the concept that "carcinogenesis and neurodegeneration may be at opposite ends of a common pathologic process," meaning that the processes that lead to memory loss and Alzheimer's overlap with those of cancer; it could very well be an “either-or” scenario.

But it's also really important to note that, as the researchers explained, the participants in their study who lived long enough to develop cancerand then continued living long enough for them to study their memory decline afterwardmay have had better memories for the same reason that they were able to live through cancer: they were healthy.

"The same factors that promote cancer survival may also prevent [Alzheimer's]," the researchers wrote. "Consequently, selective survival of healthy individuals could generate a spurious association between history of cancer and [memory function]."

To know for sureand to really pinpoint the reasons for study's resultsthe researchers recognize that "replication of these findings in other cohorts with multiple assessments of cognitive function over time is warranted." That isthey need to repeat the study, and in different populations of people.

But either which way, it can be empoweringespecially in the midst of the other challenges associated with cancerto hold onto the fact that there's a good chance your memory is superior to your cancer-free counterparts, and will continue to be well into your old age.

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.